A downward-spiraling economy is accelerating what had already been a rapidly developing trend for startups to introduce online payment methods as alternatives to bank cards.

Indeed, one such company, Miami-based Mazooma Inc., launched a cash-based commercial service on Tuesday with the premise that consumers are looking for ways to buy online without using credit.

“It’s a Zeitgeist product right now,” says Sean Kelly, chief executive of Mazooma and a former retail entrepreneur, referring to what he sees as a consumer trend toward cash and frugality. “If you don’t have the money you don’t want to spend it [on credit].” Kelly says 12-employee Mazooma currently processes for seven online sellers, but expects to bring on another 20 to 25 that are in the “integration queue.”

Helping in the effort to attract merchants is Mazooma’s inclusion in the widely used Centinel platform managed by CardinalCommerce Corp. The platform, which features a number of alternative-payment and online-authentication products, allows client merchants to more readily adopt new payment methods. Mazooma is seeking more such deals with gateways and third-party processors, Kelly says.

But Mazooma is entering a crowded market that seems to attract more companies by the week. Just last week, Amazon.com Inc. launched the commercial version of its Flexible Payments Service, a product that allows wide-ranging customization by merchant developers and handles payments through multiple channels (Digital Transactions News, Feb. 5). And this week, Noca Inc., a startup founded and run by a former Visa Inc. executive, announced its beta version of a service that relies on the automated clearing house network.

The challenge for Mazooma, as well as for its many competitors, is getting consumers to change ingrained behavior patterns while online. “From a branding and behavior-change perspective, it’s going to be difficult in the early going,” says Bruce Cundiff, director of payment research and consulting at Pleasanton, Calif.-based Javelin Strategy & Research.

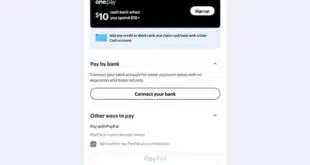

Mazooma is betting on more than the sour economy to attract consumers and merchants. Its service allows consumers to use their online-banking programs to pay merchants by authorizing a transfer from their demand deposit accounts to a holding account maintained by Mazooma. The company then wires payments to merchants, with next-day settlement. Transactions are authorized and authenticated through the online-banking system used by the consumer, but Mazooma doesn’t offer a funds guarantee to the merchant. “It’s extremely difficult for the consumer to repudiate [these transactions],” Kelly says. “It’s not guaranteed, but it’s as close as possible without being guaranteed.”

The fee to the merchant starts at 1% for very high-volume retailers and goes up from there. A merchant in the range of $30 million to $40 million in annual sales would pay about 1.5% plus 20 cents, Kelly says.

To make the system work with as many consumer accounts as possible from the start, Mazooma offers connections to 14 major banks representing what Kelly says amounts to 70% of the country’s checking accounts. “And it’s growing,” he says. Unlike other payments systems that rely on online-banking programs, for example, the Secure Vault Payments product now in a pilot sponsored by NACHA, the regulator of the ACH network, Mazooma’s service establishes no formal ties to the banks. Instead, it uses consumer log-in credentials to initiate an automated session with the chosen bank program to verify identity and funds availability. “We act as an intelligent agent for the consumer,” says Kelly. Mazooma’s servers, he says, do not store these credentials. “There’s nothing to breach,” Kelly says.

As a result, Mazooma is designed for spontaneous online transactions rather than functions like recurring bill payments. To use Mazooma, consumers at checkout click on a Mazooma button with the tag line, “Would you like to pay directly from your bank account?” First-time users are asked to fill in five fields of information, including name, address, and date of birth, and to create a password.

After that, Mazooma handles the log in to consumer accounts in the background and returns a confirmation to the consumer and merchant. Merchants must integrate a Mazooma application programming interface, a process Kelly says can take five hours, more for some merchants.

With the system in place, consumers are briefly redirected to Mazooma’s servers but believe they are on the merchant site throughout the session. The “intelligent agent” model may make for a smooth consumer experience, but it could present complications with consumers worried about malware that could enable links that appear to be legitimate but aren’t.

The Mazooma model is “a double-edge sword,” says Cundiff. “How do I know I’m really connected to [my bank] right now? I’m popping my log-in in there, and I don’t know what I’m popping it into.” Still, Kelly says Mazooma’s timing may have been just right. “The credit crisis is terrible, but we’ve had a ton of attention over the past few months,” he says. “Mazooma is a great product for the time.”