Familiar is easier than unfamiliar.

This basic truth explains much misspent effort in the payments world. Wallets are familiar. We all have them. So as it became clear that the physical part of payments—cash, checks, plastic cards—would at some point disappear, it was natural to carry the idea of a physical wallet into the digital world.

Remember the video from a few years back, from the now defunct Softcard? Back when they were Isis? It showed someone leaving home, not needing a house key, and managing all the day’s activities thorough a phone-based wallet that opened doors, acted as an ID, and paid for stuff. Really cool idea. Kind of futuristic.

But it has a few problems, both practical and conceptual.

The practical problem pertains to using a phone to replace a card swipe at a physical point of sale, that is, a proximity payment. This is something Google Inc. and PayPal Inc. have tried for a while, and Apple just started with Apple Pay. And the problem is that few people care.

Why? Because you’re asking them to change a behavior that virtually no one thinks is a problem. Ask yourself when you last heard someone complain about the complexities of swiping a card. Can’t recall? Neither can I, because no one does.

I think about changing behavior as a P&L: There is the benefit from the change, or what we might call the revenue, offset by the effort to make the change, the expense. The P&L has to be positive for many people to make the change. And with proximity payments, that is rarely the case.

True, for a very few of us, the cool factor adds to the revenue side of the P&L. But for most, there isn’t much revenue in paying with a phone. And on the expense side, at best the expense is zero, that is, the effort is the same as swiping a card.

Add to that pure habit—if you do something new only one time out of 10 instances, you are unlikely to change your behavior–and the practical problem becomes clear. The reason to change behavior is rarely compelling, and the frequency with which one can do it is low because the number of points of sale equipped with near-field communication is low. So behavior doesn’t change.

Samsung’s integration with LoopPay will broaden the opportunity for the changed behavior (most terminals versus only those enabled for NFC), but it doesn’t change the P&L. Sure, there\'s lots of talk about combining loyalty and couponing to make that P&L more positive, but to date it is just talk.

And here’s where the conceptual problem comes into play. I don’t think we need wallets in a digital world.

The wallet concept grew out of the physical world, in which one needed a container to carry stuff to the different places where that stuff needed to be used. It arose from a set of circumstances having to do with quasi-universal tokens needed for multiple uses. This is testimony to the success of the card networks. They built a vast network of places where you can use their payment tokens.

But let’s take payments. Nobody says, “I want to go and pay.\” Rather, one says, “I want to do something that requires payment to complete.\” The activity is the objective, not the payment. And in a digital world, the payment can be built into the desired activity.

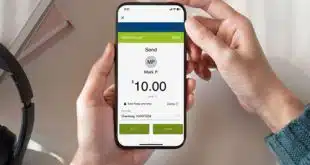

The current poster child for this is the ride-sharing app Uber. You don’t need a wallet to use Uber. The payment is built in. You don’t think about it. In other words, the payment is in-app. And that\'s where I think the future lies.

If you use Uber and have Apple Pay, you’ll see what I mean. Uber has integrated Apple Pay so it seamlessly becomes part of the desired activity of getting from one place to another. Sure, you could argue that Apple Pay in this case is a mobile wallet, but really you’re not bringing a container to the desired activity. The step needed to complete the activity is just there when you need it.

This conceptual problem—the wallet metaphor—is as much a hindrance as the practical problem, since it locks innovators into a needlessly tight box. Why try to build some universal wallet, with IDs and loyalty and payments, and with all the incumbent integration challenges? Why not just let the owner of the desired activity—the restaurant, the retailer, the nightclub—build its own app, and integrate the bits needed to complete the activity via an application programming interface?

We’re at early stages, and there\'s much more change to come. The sooner we shuck the husks of the physical past, the sooner we’ll see some really cool stuff that most of us care about.

David True is managing director of Broadly Curious Advisors, New York.