The firms that make payments apps work behind the scenes are facing a growing problem. As more and more consumers use the apps, more and more banks get involved, casting an ever-widening net of unique requirements on the data networks that connect the apps to users’ bank accounts.

That places constraints on an increasingly popular trend known as open banking. “If this is a problem with a handful of banks, how is anyone going to handle hundreds or thousands of banks?” asks Ben Isaacson, a senior vice president at The Clearing House Payments Co. LLC, which this week launched a service to simplify the process. TCH, owned by 24 of the nation’s biggest banks, has piloted the solution, which it calls the “Streamlined Data Sharing Risk Assessment,” with seven major banks and two data aggregators, Plaid Inc. and Finicity Corp., which is now part of Mastercard Inc.

The key to the new approach is a common questionnaire that all participating banks agree to accept from each data network or financial-app developer. That approach replaces the current process, in which each bank requires that its own unique form be completed. As financial apps proliferate and grow in popularity, that method is creating a problem for aggregators and developers alike.

Aggregators, which specialize in connecting developers with financial institutions, “are not huge companies,” says Isaacson. “They don’t have a ton of resources.” Yet they must meet the unique due diligence and risk-management requirements of a rapidly growing roster of financial institutions. “That was really putting a strain on the data aggregators’ business,” Isaacson says. “It’s not like they have thousands of risk folks.”

Financial institutions had started to recognize the problem, too, as more financial apps emerged and more requests came in to establish connections to users’ accounts. “Risk is never the place where a bank first invests in resources, so from the banks’ side this was becoming a problem too,” Isaacson says.

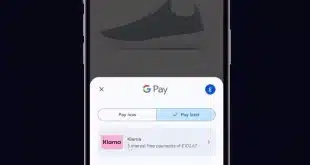

Companies like Square Inc. and PayPal Holdings Inc. have introduced popular apps that allow users to transfer funds, pay merchants, and, for some, to buy cryptocurrency. In almost all cases, such features require connections to users’ bank accounts. The growing popularity of such apps has made the simplified vetting process a crucial matter, TCH says. “This is a critical issue for the industry to scale,” Isaacson says.

Especially so, he adds, as more and more technology firms approach their customers’ banks directly, adding to the requests coming in from the data aggregators. “It’s starting to expand to fintechs, as well,” says Isaacson.

With its new service, TCH hopes to solve that scalability issue. But the process hasn’t been easy. Getting the common form done so that it could be accepted across the spectrum of financial institutions was “the hardest part, frankly,” Isaacson says, in part because of due-diligence and other regulatory requirements banks must meet. But, Isaacson says, with the new approach “banks aren’t outsourcing risk management, they’re outsourcing the collection of data.”

To make that point, TCH has recruited TruSight and KY3P by IHS Markit, assessors that pore over questionnaires to verify the information aggregators have filled in and that also conduct onsite visits. “That’s where all the hard work is,” Isaacson says. TruSight also participated in the pilot.

Companies like Plaid and Finicity have grown fast in recent years as consumers have adopted financial apps in droves. Plaid alone saw its number of linked accounts balloon from 10 million in 2015 to more than 200 million by 2019. Visa Inc. late last year withdrew a $5.3 billion bid to acquire Plaid after the U.S. Department of Justice sued to stop the transaction on antitrust grounds. In the fall, Mastercard acquired Finicity for $825 million.