Our daunting set of sticky wickets this time ranges from data breaches that just don’t stop to debit card pitfalls to travails for P2P and Bitcoin.

This is Digital Transactions magazine’s 11th annual ranking of payments woes, and one lesson we’ve learned in all that time is that they don’t get any easier.

This year, the top three issues on our list have to do, one way or another, with the threat of fraud. Data breaches, which first hit payments executives’ radar screens more than a decade ago, show no signs of relenting. And they continue to penetrate major data repositories—just ask Equifax and Yahoo.

And now more recent developments must be reckoned with. The Federal Reserve has set a target of 2020 to achieve a national faster-payments system. But flowing payments in real time means fraud has to be detected in the blink of an eye. Meanwhile, the fast-developing Internet of Things network of devices presents yet other risks, as we detail below.

Elsewhere, we find a miscellany of menaces. These include hoary issues like non-banks trying to muscle in on bank territory as well as brand-new developments like the sudden waning of debit card growth and the scramble to make money on peer-to-peer payments. Read on to find the details.

One cause for cheer in all the gloom is the continued robust growth of the business overall. By our estimates, the industry last year posted 137.2 billion consumer-based ATM, ACH, and card transactions, up a respectable 4.6% from 2015. But there’s even a downer in this news: that growth rate was noticeably slower than the year before, which clocked in at 6.3%.

- Endless Data Breaches

Perhaps the old saying that only two things in life are certain, death and taxes, should be modified to add a third: data breaches. Despite PCI security rules, end-to-end data encryption, tokenization, and other technological prophylactics, hackers continue to break into computers and steal payment card and other financial and personal data about consumers.

From 2005 until early October, the Identity Theft Resource Center, a San Diego non-profit, says there were 7,954 data breaches that exposed 1.05 billion records containing such information as individuals’ names, Social Security numbers, driver’s licenses, or financial or medical records. (The ITRC’s record total excludes thefts of user names, email addresses, and passwords that don’t involve sensitive personal identifying information.)

Data breaches have been around since the dawn of the Internet era, but for merchants, payment card issuers, and merchant acquirers they became a serious fact of life in the wake of the 2005 breach at processor CardSystems, the hack at retailer TJX disclosed in early 2007, and the biggie at acquirer Heartland Payment Systems Inc. in 2008 that compromised 130 million card numbers. Since then, Target, Home Depot, and scores of other merchants have joined them.

The breach reported in September by Equifax Inc. could have the most far-reaching effects of all because the 145 million records exposed in the credit-reporting agency’s computers, excluding 200,000-plus payment cards, included all the elements fraudsters need to create fake identities, including Social Security numbers.

The cure? Certainly constantly improving security technology will help, but compensating for human vulnerabilities with better training and better awareness of fraudsters’ tactics is needed at least as much. At a Congressional hearing, Equifax’s now-departed chief executive tried to affix blame for the breach on a single employee who supposedly failed to make sure that a vulnerable software application had been patched. But few bought the argument that the disaster could be traced back to just one guy.

- Do Faster Payments Mean Faster Fraud?

The U.S. faster-payments initiative has all the hallmarks of becoming a transformative component for commerce and transferring value. The long-sought-after goal of clearing and settling payments in near real-time is nigh. The Federal Reserve, which sponsored the Faster Payments Task Force that shepherded development of faster payments, calls for speedier payments by 2020.

Ultimately, 16 proposals were included in the task force’s final report.

One big unknown is just what sort of fraud any faster-payment regime may attract. Faster payments will bring changes throughout the payments industry, and these changes may entice criminals, especially as the window to verify a transaction shrinks.

“With existing ACH payment systems, funds don’t fully settle into destination bank accounts for two to five days, this gives fraud-monitoring teams time to review transactions and listen for customer complaints before releasing funds to a destination account,” Tristan Kenning, head of product at payments provider Bambora North America, says. “When payments are faster and funds settle in real time, the opportunity for review closes, meaning fraud can occur in real time and funds are withdrawn from the destination bank instantly.”

Measures such as automated fraud monitoring, which involves machine-learning and device-fingerprinting tools, could help. Another is educating banks, fintechs, and consumers.

“Customers, banks, and fintechs alike will need new measures to protect themselves. Looking overseas at the United Kingdom’s faster-payments scheme, we can see how seriously the U.K. government has positioned its own ‘Take Five’ public-awareness campaign,” Kenning says. Among that campaign’s purposes is educating consumers to make sure the funds’ destination is legitimate and aligns with requestor or seller, Kenning says.

After all, as Kenning adds, “Once the funds are sent, it is very difficult to retrieve them.”

- The IoT: Friend or Foe?

Various research firms have called the Internet of Things everything from a $14 billion opportunity for payments firms to “an unmanageable cybersecurity risk.” Just about everyone, however, agrees that the IoT is here to stay.

Broadly defined, the IoT is everything connected to the Internet that isn’t a traditional mainframe, desktop, laptop computer, smart phone, or tablet. This network, which will connect anywhere from 15 billion to 30 billion devices in the next few years, depending on who’s counting, includes a rapidly growing fleet of automobiles, household devices, appliances, toys, and personal items. Think of the rather pricey Samsung refrigerator that, with the help of Mastercard, can detect which food items are getting low, then compile a grocery list and do the ordering and paying.

The problem with the IoT is that many new connected devices are taking on payment functions without data security top of mind at the manufacturers and software developers creating applications for them. The fraud possibilities seem endless. Just over a year ago, in the so-called Dyn attack, cyber-attackers assembled a network of connected devices to execute a huge digital denial-of-service assault that temporarily shut or slowed down a number of major U.S. and European Web sites.

The PCI Security Standards Council is working on recommendations for IoT security, though it hasn’t yet issued actual rules that would be mandatory for card-accepting merchants and processors. What happens after the next big IoT-linked data theft, however, might spur calls for a more active security approach by the payments industry.

- More CFPB Regulation?

The prospect of more regulation from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is never appealing.

Still, while the CFPB under President Barack Obama may have come on seemingly full bore against the payments industry, the agency is more restrained under President Trump’s tenure. And, even outside of the executive branch, the agency is feeling more pressure than it’s accustomed to.

Earlier this year, for example, a federal judge tossed CFPB allegations against payment processors serving allegedly fraudulent debt collectors. The reason? The judge agreed with the processors that the CFPB tried to avoid answering questions during the deposition part of the case, sometimes by asserting privilege even after the court ordered it to answer, and failed to produce a knowledgeable witness who could explain the CFPB’s case.

Still, the regulator has potentially impactful legislation in the winds. The effective date for its massive rule for prepaid accounts has been pushed back officially to April 1, 2018, from its original Oct. 1, 2017, date. Earlier this year, in public comments, several prepaid providers called for an April 1, 2019, implementation date because of the complexity of prepaid accounts. But with or without further delay, the rule is coming, and will impose a much heavier hand on prepaid payments than the industry has ever had to contend with.

What’s next for the CFPB may depend on how the payments industry evolves. Speaking at the Electronic Transactions Association’s Strategic Leadership Forum in October, Dan Quan, a senior advisor to CFPB director Richard Cordray, said, “We see innovation, a large amount of innovation, happening from the market outside the traditional banking system, and a lot of these innovations have the potential to really improve consumers’ financial lives.”

The question now is not whether, but how, the CFPB will shape this innovation and improvement.

- The Threat to Debit Cards

If you had to name the most popular consumer payment products of the past 25 years, the debit card would have to rank pretty high, maybe even number 1. Banks like them, too, and no wonder. They generate 70 billion U.S. transactions annually, throwing off billions in interchange income. And, for banks with less than $10 billion in assets, that interchange is exempt from the Durbin rules that cap debit card interchange for big banks.

But these days, the debit card is under siege. Growth has come to a screeching halt, as transactions increased just 1% in the first quarter compared to the same quarter in 2016, according to data from the networks. By contrast, that growth rate was fully 11.51% from the first quarter of 2015 to the first quarter of 2016.

What’s going on? Rival products are growing. The number of credit card accounts, for example, is approaching 460 million, a level last seen in 2008 on the eve of the financial crisis, according to a report from Mercator Advisor Group, citing Federal Reserve Bank of New York numbers. Increasingly, credit card holders are using the cards as a form of deferred debit, paying off their balances in full each month, the report says.

It’s not just credit cards jockeying for debit card volume. Decoupled debit programs are becoming more appealing with the advent of same-day processing on the automated clearing house network, says the Mercator report.

Another potential threat is the so-called request for payment, which has been deployed in other countries and is seen as part of the wider trend toward faster payments. This method allows merchants to text or email a payment request to customers at the time of purchase. Once authorized on the spot, funds move to the merchant’s account within seconds, according to the report.

- Mobile’s Doldrums

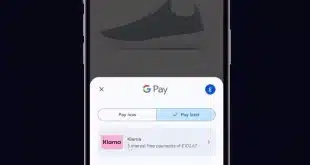

In the three years since Apple Inc. launched its Apple Pay mobile-payment service, quickly followed by Android Pay from Google and Samsung Pay from Samsung Electronics, there’s been lots of talk about them. Millions of consumers can use them to make contactless payments in the blink of an eye. Merchants can accept them to speed up checkouts. Since the launch of these so-called Pays, retailers and banks have come out with their own mobile-wallet services.

But, and this is a big but, only a small percentage of consumers actually use any of the services. According to a Javelin Strategy & Research report from earlier this year, only 5% of consumers used a mobile wallet at least one a week. Adoption has plateaued, too. It’s an issue for the payments industry. Not only have mobile-wallet providers invested heavily in the technology, so too have processors, acquirers, and merchants.

So what’s the problem? As one Android Pay executive put it, lackluster usage may be blamed on several factors, including spotty availability at merchants, a lack of consumer awareness, and questionable value. Others suggest consumers want speed and convenience, qualities they don’t perceive as associated with mobile payments because of misreads or other missteps at the point of sale.

Yet, elsewhere in the world, mobile payments are doing well in terms of adoption. In Australia, the United Kingdom, and Canada mobile payments—in the form of contactless cards—are widely used by many consumers. Internationally, Apple Pay use surpasses that in the United States.

Indeed, 75% of Apple Pay transaction volume originates in other nations, Apple said. Of the near-field communication-based mobile-payments services—Apple Pay, Android Pay, and Samsung Pay—Apple claims 90% of all transactions globally are made with its service.

- Fuel-Pump Frustration

Bringing U.S. fuel pumps into the age of EMV chip cards is proving to be a high-octane headache for gas stations and their payment-services suppliers. The bank card networks knew the job of retrofitting pumps was a big one when they set their U.S. EMV point-of-sale liability shifts for October 2015, but delayed corresponding shifts for automated fuel dispensers until October 2017.

After all, fuel pumps are more complex affairs than POS terminals, and sometimes they’re too old to take chip-card-accepting upgrade kits, thereby requiring breaking concrete to remove an old pump and install a new one. One consultant estimates the cost of the U.S. fuel-pump retrofit at $6 billion.

But even the extra two years proved to be not enough time. Late last year, Visa and Mastercard heeded cries for a delay by postponing their fuel-pump liability shifts for another three years, until October 2020.

While the postponements bought convenience stores and gas stations more time, they caused problems for others. POS terminal makers such as VeriFone reported that delays in orders for their EMV fuel-dispenser equipment were crimping their near-term revenues, though they eventually expect to make them up.

Fraudsters might be the biggest winners in the interim because, as the number of fraud-resistant EMV card-accepting locations grows, unattended fuel pumps will be increasingly attractive locations for placement of skimmers that capture magnetic-stripe credit and debit card data. Such data can then be harvested for fraudulent online purchases or creation of counterfeit cards. In large part because of higher fraud at fuel pumps, fleet-fueling card specialist WEX Inc., whose cards are accepted at most U.S. gas stations, upped its second-quarter provision for credit losses by 150%.

WEX said it was working hard to control the problem and that it expects fraud losses to taper off by year’s end. But WEX is far from the only one getting hit by fuel-pump fraud, which means that for many payment companies, October 2020 can’t come soon enough.

- Non-Banks as Banks

In the payments industry, some issues never die. Take the dust-up merchant processor Square Inc. provoked in September when it filed for a Utah industrial bank charter. Predictably, some bankers cried foul, arguing that a non-banking firm can escape the heavier regulation conventional banks endure by getting a Utah charter, thereby giving them an unfair market advantage.

This debate pitting the banking establishment against outside challengers goes back to at least 1990, when AT&T introduced the AT&T Universal Card, a cobranded credit card, to huge fanfare. The actual issuer was a little specialty bank called Universal Bank, which was owned by the bank-holding company Synovus Corp.

What made the program so controversial was that AT&T bought Universal Bank’s card receivables daily and performed such functions as customer service, raising questions about who was really calling the credit-related shots—the bank issuer or the non-bank cobranding partner. The debate sharply divided the card industry.

Despite the row, AT&T sold the Universal Card portfolio to Citibank in 1997 in what amounted to a triumph for the establishment. And bank opposition to Wal-Mart Stores Inc.’s plans of a decade ago to own a bank was so strong that the No. 1 retailer dropped the matter.

A Utah bank charter would enable Square to offer merchant cash advances and loans directly to its sellers through its Square Capital service. Square currently uses Celtic Bank, itself a Utah industrial bank, to fund Square Capital. Square has played up the prospects of lending to credit-starved small businesses when talking about the bank charter, but it might enable Square to act as its own merchant-acquiring bank, too.

Another financial-technology firm, Varo Money Inc., also is seeking a bank charter. Might it and Square claim some turf currently held by regular banks? Probably. But will they upend the banking industry? Given the experiences of AT&T, Wal-Mart, and other bank wanna-bes, probably not.

- P2P Payment: Where’s the Money?

All of a sudden, mobile person-to-person payments are all the rage. And for good reason, as total U.S. mobile P2P volume is expected to soar 10-fold over five years, from $37 billion last year to $336 billion in 2021, according to forecasts by researchers at BusinessInsider. Just this year, volume will climb a robust 62%, to $60 billion.

Growth like that has got the attention of the nation’s biggest banks. In June, their commonly owned P2P network, Zelle, officially launched to do battle with PayPal Holdings Inc.’s wildly popular Venmo service. Banks fear losing out in mobile P2P because the service tends to attract the highly coveted Millennial crowd.

But Zelle, Venmo, and lesser services share one problem in common: they’re fighting over a market that produces virtually no revenue. Since the whole point is to win volume away from the rival service, everybody’s afraid to charge fees for something that has been free since it started. PayPal has attacked the issue by making Venmo work for purchases in-app or on the mobile Web at up to 2 million PayPal-accepting merchants. That way, PayPal can collect its standard merchant rates, which start at 2.9% plus 30 cents and decline with volume. The company is also beta-testing a Venmo-branded plastic debit card that can be used at physical checkouts.

Zelle, meanwhile, is simply enrolling more and more users. By September, the network said it was adding 50,000 customers every day. Its advantage is that funds flow directly from bank account to bank account in a matter of minutes. Venmo is fast, too, but recipients have to take an extra step to move funds into their bank accounts.

But so far Zelle has been a phenomenon of the nation’s largest banks. Community banks and credit unions aren’t seeing much mobile P2P action, according to a recent report from Malauzai Sofware Inc., an Austin, Texas-based mobile-technology vendor for smaller institutions. According to the company’s figures, only 1.2% of active digital-banking users at its clients are making P2P payments, regardless of device.

“Lots of hype and no results,” says a report Malauzai released in October.

- Bitcoin’s ‘Bubble’

The Bitcoin story can be summarized very briefly: at the start of the year, it was trading at around $1,000. By the time of this writing, in mid-October, its price had more than quintupled, making some early investors in the 8-year-old cryptocurrency quite wealthy. But lost in all the pricing hype are two questions: is the bull market really just a bubble, and whatever happened to Bitcoin as an electronic payment method, which, after all, is supposed to be its main purpose?

As with any investment, nobody can foretell the future, even the immediate future. In September, Jamie Dimon, chief executive of JPMorgan Chase & Co., went to a financial-services conference and called Bitcoin a “fraud” and its price appreciation a “bubble” akin to the infamous tulip-bulb mania of the 17th Century.

Dimon didn’t get where he is by being wrong about finance too many times. If he’s right, though, it may not matter how many merchants do or don’t accept Bitcoin. Users won’t be able to see them through their tears.