It’s coming sooner for some players than for others. Here’s why—and how to be a survivor.

By John Stewart and Jim Daly

If you’re a purveyor of mobile wallets or a vendor of mobile-acceptance gear, you don’t have to be told that you have plenty of company. What’s less clear is just what combination of attributes will lead to success in these distinct but related—and very crowded—markets.

For as sure as Alexander Graham Bell invented the telephone, a culling of the herd is inevitable. “Most of the players will fail, for sure,” pronounces Drew Sievers, chief executive of mFoundry Inc., a mobile-payments and –banking software house in Larkspur, Calif. Others will be swallowed up by bigger or richer entities. A few will survive to dominate the business.

Opinions vary wildly on how soon the shakeout will happen. These are still very young—not to say immature—markets, after all. Some say a year or two, others look to a five-year horizon. All agree it’s inevitable.

Mike Orlando, the new chief sales officer at Palo Alto, Calif.-based startup Jumio Inc., and a veteran of CyberSource Corp., says “the prospects for mobile payments are huge, which is why so many players are trying to enter it.” Jumio’s app lets consumers make card transactions by capturing video of their cards with their phone or computer Webcam.

But not all will make it, Orlando says. “I do believe there is going to be consolidation in the industry,” says Orlando. “Certainly not everyone is going to survive.”

Manifold Problems

For this story, we are looking at two distinct markets with one thing in common: they have both attracted—and continue to attract—a bevy of providers, both startups and established companies. These are the mobile-acceptance (think dongles) and digital-wallet markets.

On the digital-wallet side, no single company, established or startup, has found the key to adoption. This includes mighty Google Inc., whose mobile wallet has languished among both consumers and merchants. “Some are too new or came out too soon or don’t have the right value proposition,” notes Mary Monahan, managing director at Javelin Strategy & Research, Pleasanton, Calif. “It’s hard enough for the big guys.”

And new players continue to flood in, seemingly by the day. Depending on how you define a wallet, there are at least 40 and as many as 120 currently available in the United States alone.

Certainly, the market opportunity looks vast. Worldwide, the total value of wallet-based transactions in stores is expected to balloon from $3 billion this year to nearly $300 billion by 2017.

Wallet startups spend their days trying to crack an age-old problem in payments—signing enough consumers to interest merchants, and enough merchants to get the attention of users. “Until a company hits that place of ubiquity, we’re going to see fragmentation,” says Matt Kiernan, marketing manager at LevelUp, a Boston-based startup.

But fragmentation can’t last for long. It’s indeed early days, but already signs of consolidation are emerging, and some players have fallen by the wayside. Early consumer-oriented pioneers like Obopay Inc. and Bling Nation are gone or for sale, for example.

“There will be a ton of shakeout in that space,” says mobile-payments veteran Jon Squire, who hopes to be among the survivors with his new wallet company, CardFree. The San Francisco startup in November clinched $10 million in Series A funding. “It’s daunting,” Squire adds. “You’re either in this to be acquired very quickly or dominate or own it.”

The manifold problems confronting wallet purveyors begin with the uncertainty surrounding mobile payments’ fundamental technology—the triggering mechanism that sets payments and loyalty transactions in motion. For years, the Holy Grail has been near-field communication, or NFC, a short-range radio-frequency identification technology that sets up a two-way link between a handset and a terminal or any other device embedded with an NFC chip.

That allows for fast transfers of all sorts of data, including payment, coupons, discounts, and loyalty points. Consumers could receive new points and redeem old ones in one transaction.

‘Fake Cows’

But startups could exhaust the patience of their backers waiting for NFC to arrive. Elegant as the solution may be, nobody wants to assume the cost of deploying it. The scarcity of NFC terminals has led even established companies to turn away from the technology. Last summer, Google refashioned its Wallet to move card credentials out of a chip in the phone to a server-based wallet, for example.

Apple Inc. dealt NFC another blow last fall when it launched its highly anticipated iPhone 5 without the requisite chipset. Again, Apple saw lots of wallets but too few places for iPhone customers to use them. Such is the downdraft from this decision that Juniper Research, a U.K. firm that follows NFC, lowered its projection for worldwide NFC-based payments volume by fully 39%, from $180 billion to $110 billion. And that’s by 2017.

NFC may stage a comeback by then owing to a rule from the card networks meant to support EMV, the global chip card standard. Starting in October 2015, liability for counterfeit card transactions will shift from the issuer to the merchant if the merchant hasn’t deployed an EMV-capable terminal. Since such devices will likely also have NFC capability, the EMV rule is expected to help populate merchant points of sale with NFC.

But that’s some time out. In the meantime, many wallet purveyors are making do with barcodes. Merchants tend to have the equipment already in place, and the experience for the user is nearly as quick and easy as NFC. “Becoming mainstream is all about accessibility,” says LevelUp’s Kiernan. “Right now it’s the QR code. If there comes a time when NFC is ubiquitous, then we’ll integrate it.”

Others, like Square Inc., are relying on geolocation. The Square Wallet activates when the user is within a few yards of the store. Later, when he approaches the checkout counter, all he has to do is utter his name, and his merchandise is charged to the card he has designated.

Still others, like Chicago-based Braintree Inc., are relying on proprietary technology. Last year, the company bought Venmo Inc., a New York City-based startup specializing in person-to-person payments. But it also enables transactions for e-commerce merchants selling what chief executive Bill Ready calls “a real good or service, not fake cows or chickens.”

Ready says Braintree is relying on its tech. “Technology will drive who wins in [this] space,” he declares.

“Ubiquity” is a word you hear often when talking to wallet companies. They all want it—ubiquity among both consumers and merchants—and fast. “Payments is a scale game—that’s where they’ll be up against a boulder,” says Cherian Abraham, who follows mobile payments as senior business consultant at Experian Decision Analytics in Atlanta.

Among wallet companies, many will fail because they’ll have been rolled over. Payments consultant Steve Mott, who keeps a list of wallets, says the number that offer open access to most payment methods comes to 42—as of December. “Certainly a number of the 42 are in the living-dead category,” he notes, because they can’t figure out how to scale up.

Finally, it may be relatively cheap to get in on the ground floor of a wallet startup, but those days are numbered. Backers will soon start expecting to see adoption, and plenty of it, among both consumers and merchants. “Much of the innovation has been tied to free-flowing private-equity money. That’s going to dry up,” says Abraham. “The question wallets will have to answer is whether they’ll see traction beyond the hoopla we’ve seen so far.”

So what characteristics will separate the survivors from those who fail or get acquired? Sources contacted for this story point to these four winning attributes:

1. Money. Enough said.

2. Technology. This involves not just figuring out the NFC conundrum, but also deploying tech that lets merchants penetrate their customers’ shopping habits. Experts call this “visibility.” Google, for example, has it because of the data collected by its massive search engine.

3. Paths to widespread consumer adoption. Wallets may be concentrating on merchants to start with, but the ultimate key to success will be signing users en masse. “The real value is in the consumer activation of the product,” says Rick Oglesby, a senior analyst at Boston-based Aite Group.

4. Overwhelming brand equity. Not only will the brand have to convey trust among consumers, it will also have to evolve into a mark at the point of sale, a signal that the wallet can be used here. “As we debate technology, the [brand issue] tends to be glossed over,” says Ken Paterson, vice president at Mercator Advisory Group, Maynard, Mass. “It will be like the early days of credit cards. There will have to be some sort of acceptance mark.”

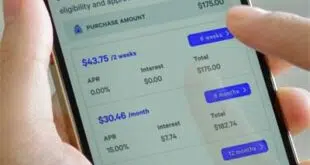

Wallets will have to devise strategies to go with these attributes. Visa Inc., for example, is already attacking the consumer-adoption issue for its V.me digital wallet by integrating it with the online-banking systems of the financial institutions that offer the product. That automatically populates the wallet with consumers’ payment credentials, making adoption easier, says Shaun Bodington, Visa’s head of V.me.

VeriFone Trims Its Sail

On the mobile-acceptance side of the business, the dynamics are different, but here too early signs of a shakeout may be emerging. On Dec. 13, for example, leading U.S.-based point-of-sale terminal maker VeriFone Systems Inc. threw in the towel as the merchant acquirer for its Sail mobile-payments platform for micro-merchants, just seven months after launching the service.

“Acquiring for these merchants is unprofitable,” chief executive Douglas Bergeron told analysts during VeriFone’s earnings conference call for fiscal 2012’s fourth quarter. “The assets that we have developed around customer acquisition, risk management, and customer billing will be divested.”

Instead, the San Jose, Calif.-based firm will revert to its more traditional, and profitable, role as a solutions provider to merchant-acquiring banks, independent sales organizations, and large retailers.

VeriFone plans to provide Sail-branded services to banks and ISOs, which it says have now stepped up in sufficient numbers to sign micro-merchants and process transactions for them. In November, for example, VeriFone introduced Sail EMV, a chip-and-PIN mobile-payments solution for small and medium-size merchants—marketed through acquiring partners.

VeriFone had handled the acquiring role itself since Sail’s May 2012 launch, apparently through its little-known, in-house ISO, VeriFone Merchant Services LLC, to fill what the company called a void created by banks and acquirers slow to move into the micro-merchant channel. VeriFone Merchant Services feeds its transactions to processor Vantiv Inc., and its sponsor bank is Fifth Third Bank.

Sail was a direct-to-user payment solution intended to provide micro-merchants a single source of end-to-end payment services. VeriFone offered two pricing plans, a flat 2.7% per transaction for purchases initiated through a Sail card swipe on a mobile device, or a monthly subscription rate of $9.95 plus a 1.95% per-transaction fee.

Bergeron believes successful acquirers for micro-merchants will use payment processing as a loss leader to sell value-added services. “But we don’t want to be the company that finds and pulls micro-merchants into acquiring and have to manage the risk on top of it,” he said.

Taking on Square directly proved harder than VeriFone expected, according to mobile-payments consultant Todd Ablowitz of Centennial, Colo.-based Double Diamond Group. “This tells us is that the strategy of going head to head with Square is a silly thing to do,” he says. “They have a long lead, fabulous marketing, and a very low-cost operation.”

Following the Spreadsheet

While some saw VeriFone’s trimming of Sail as a retreat, Bergeron’s comments bluntly reflected what many ISO executives have been whispering in the face of fawning headlines about Square’s latest move or the entry of yet another player in the micro-merchant space: that it’s hard to make money from tiny merchants because of the lack of scale and high risk.

“The one thing I will give VeriFone credit for is being quick to act,” says Henry Helgeson, chief executive of Merchant Warehouse, a big Boston-based ISO. “I think this was a very tough decision for them to grapple with. They followed their spreadsheet, not their emotions.”

Back in 2009, in the earliest days of smart-phone payments services for pint-size merchants, Merchant Warehouse began offering a free payments application in Apple’s App Store bundled with a merchant account. The processor quickly booked many new customers, but they were “transient merchants” with low transaction volumes but high attrition rates and high risks, says Helgeson. “The margins weren’t there.”

There is profit in processing for micro-, or so-called Tier 5, merchants, but only if the processor has a consumer application to complement its merchant offering, Helgeson believes. And so far, he says, only two companies are doing that: Square, which can drive consumers into Square-accepting stores with its Square Wallet app, and PayPal Inc.

“You really need both sides of the puzzle here,” he says.

But some players in this game see VeriFone’s move as specific to VeriFone, not indicative of larger market economics. Marc Gardner, founder and chief executive of the Troy, Mich.-based ISO, North American Bancard (NAB), which offers the Pay Anywhere service for mobile merchants, says there’s profit to be made from the micro-merchant side.

VeriFone, Gardner notes, never was a processor, risk manager or customer-support provider for small merchants before it rolled out Sail. “I think he [Bergeron] is correct that for VeriFone, it wasn’t profitable,” Gardner says. “Their core competency was at the enterprise-level customer.”

Pay Anywhere, in contrast, has proven to be a good business since its February 2011 launch by drawing on NAB’s experience in managing merchants, a distribution network that includes Wal-Mart Stores Inc., The Home Depot Inc., and other national retailers, and what Gardner calls a “feature-rich” solution that will be enhanced further this year.

“For us, it is profitable, all we do is processing,” says Gardner, who won’t reveal the size of Pay Anywhere’s portfolio or its charge volume (parent company NAB services more than 135,000 businesses generating $12 billion in annualized charge volume). “All of that was all new and nascent to VeriFone.”

But tech providers in the mobile-payments space echo Bergeron in saying that those that can offer a suite of services will be the ones that survive.

“[Merchants] want services beyond just a credit card transaction,” says Jason Richelson, founder and chief executive of ShopKeep.com Inc., a New York City-based company that provides cloud-based business-management software for small companies that runs on Apple’s iPad tablet computer. “That’s what retailers need, and historically card processors have not offered.”

Richelson cites time tracking, data reporting, and other value-added services. ShopKeep has business dealings with such mobile-payments providers as PayPal, Dwolla Inc., and LevelUp.

“The people that are offering that full solution are going to do fine, with a good brand and customer care,” says Richelson.

James DeBello, chief executive of San Diego-based Mitek Systems Inc., the leading provider of software for mobile remote deposit capture, says “consumers will dictate” whether a shakeout in mobile payments comes. But survivors of any such shakeout will be companies that don’t force consumers to learn new payments tricks, according to DeBello.

That’s why he’s not too keen on technologies like NFC, which require the consumer to get an NFC-enabled smart phone and the merchant to have a chip-reading terminal.

In contrast, all smart phones have a camera that consumers can use to snap a picture of a check and upload the images for deposit to their checking account through their online-banking program, he notes.

“We try to apply our technology to current, practical issues,” says DeBello. “Millions of Americans are taking pictures with their phones daily.”

And like DeBello, Jumio’s Orlando wonders about the prospects for NFC despite all the hype about the high-powered technology. “I do think there will be consolidation there, because of the limitation of the device on the other [merchant] end that’s required to accept the payment,” he says.

Meanwhile, it’s still early days, and optimism runs rampant throughout this young business. Many expect a shakeout, but few expect to be one of the victims. “We’re engineering a revolution in payments,” says LevelUp’s Kiernan. “We’re in it for the long haul.”

With additional reporting by Peter Lucas