EMV chip cards and mobile payments may be two abiding passions of the payments industry these days, but major merchants are far from sold on either technology, judging by comments from a number of them Tuesday at a payments-technology conference.

Most big retailers are gearing up for EMV in an effort to beat an Oct. 1 deadline by which they will assume liability for counterfeit and lost-and-stolen point-of-sale fraud if they can’t accept chip transactions. But that doesn’t mean they’re happy about the way the technology is playing out.

One big issue is that EMV debit card transactions will likely follow paths determined by the major card networks rather than by merchants, despite debit-routing choice mandated by the Durbin Amendment to the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act, according to Mike Cook, senior vice president and assistant treasurer at Wal-Mart Stores Inc., which began installing EMV capability as long as eight years ago.

“We have credit [EMV] up and running,” Cook told an audience of merchant processors and payments-technology executives at the Electronic Transactions Association’s Transact 15 conference in San Francisco. “Where the challenge comes in is with debit, especially [near-field communication] debit.”

With EMV debit transactions, merchant terminals must open and access two application identifiers to give the merchant network-routing choice, a global application from the major networks and a so-called common application accessing other national debit networks, according to Cook. This two-step process, he said, adds so much time to the transaction that most retailers will likely default to the global application simply to keep lines moving. This complication will be even more glaring with NFC transactions, which involve a tap or a wave of the card.

“I find it troubling that [this] makes it difficult if not impossible” for merchants to preserve their Durbin routing rights, Cook told the audience.

Under Durbin, merchants must have a choice of at least two unrelated networks for routing of debit transactions. The EMV specifications, however, don’t allow for such choice, a problem the payments industry wrestled with for months before finally settling on a solution last year. That settlement, however, came late in the game, and the industry is still struggling to catch up with software and hardware. “There isn’t a terminal in the marketplace today that can preserve the merchant’s routing rights,” Cook said.

Before Cook spoke, a panel of big merchants gave voice to other frustrations with EMV. One major theme is that EMV imposes multimillion-dollar costs for multilane merchants but does nothing to lower acceptance costs. “Our [return on investment] in EMV is negative,” said Maureen Elworthy, director for treasury at Ahold USA, which operates 766 supermarkets under the Stop & Shop and Giant Foods banners.

At the same time, the fraud it combats will represent a savings only for the banks that collect card interchange. “Ninety-five percent of the fraud EMV will prevent goes back to the issuer anyway,” said Kenneth Grogan, manager of treasury services at Wakefern Food Corp., which owns 296 ShopRite stores. “We’re frustrated with that. They need to share that savings and give us a break on interchange.”

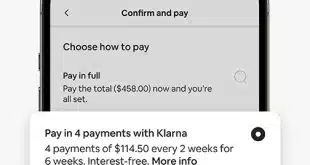

The merchants’ approach toward mobile payments is equally wary. With a number of digital-wallet providers battling for supremacy, some merchants argue it’s best simply to wait before committing to any particular product. “It’s been the year of mobile for the last six years running,” said Mario de Armas, senior director of international payments for Wal-Mart. “How many interfaces or implementations am I going to do? A merchant can’t place multiple bets. The smart thing to do is wait and see.”

Wal-Mart, however, is a founding member of Merchant Customer Exchange, the merchant-controlled operator of the CurrentC mobile-payments and loyalty app, which is expected to debut some time this summer.

Even the apparent popularity of Apple Inc.’s Apple Pay wallet has some merchants concerned that Apple will begin demanding higher fees from issuers, which in turn will pass the higher costs on to merchants with higher interchange. Currently, Apple collects 0.15% from issuers on credit card transactions and half a penny on debit.

“As a finance guy, my concern with Apple Pay is it’s another hand, it drives up costs,” said Wakefern’s Grogan. “At some point, [Apple] goes back to the banks and says this is worth more than 15 points. That gets passed back to the merchant, and ultimately it costs more to accept Apple Pay than to accept a credit card.”