While merchants, like consumers, love credit and debit cards, they don’t like having to pay to accept them. It’s human nature to want to pay less for products and services, no matter how good they are.

To reduce payment-acceptance fees, merchants have brought a battery of antitrust lawsuits against Mastercard and Visa. If successful, it would diminish the value America’s leading payment networks provide. In plain English, it’s anti-consumer.

The suits were consolidated, and then ultimately divided into a class-action suit for damages and one seeking changes in Mastercard’s and Visa’s interchange fees and acceptance rules. The Damages Class settled in 2019.

The Equitable Relief Class attacking interchange and acceptance rules is more troubling. That’s because it threatens features that create value for cardholders, banks, and merchants.

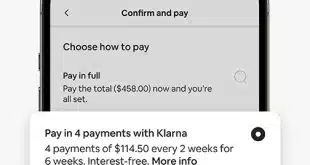

A settlement was announced March 26, 2024. However, on June 28, Judge Margo Brodie, who was appointed by President Obama, rejected the proposed landmark $30-billion settlement. Brodie declared it “inadequate,” arguing the defendants could bear a greater reduction in credit interchange. She noted that permitted surcharging’s benefit would be limited because some states ban it and because American Express prohibits it unless all credit and debit cards are comparably surcharged, and Mastercard and Visa don’t allow surcharging debit cards.

Brodie also was troubled that the settlement would have strengthened, rather than eliminated, the honor-all-cards doctrine by mandating merchants accept digital wallets owned by Mastercard and Visa.

Mastercard and Visa preferred a settlement seeking outright victory and vindication in court. Much as management may believe in the righteousness of their business practices, an outright win would have removed uncertainty for investors, customers, and the entire system. Moreover, as with Russian roulette, at trial the networks risk a catastrophic outcome.

The settlement would have given plaintiff merchants certain benefits, albeit not everything they wanted, but that’s the nature of settlements.

Now, the chances have increased that suits consolidated in the Eastern District of New York before Judge Brodie will be sent back for trial to the courts from which they originated. There, the question whether there’s an antitrust problem with America’s largest “card” networks, Mastercard and Visa, would be argued and determined.

Consumer welfare matters. Under traditional U.S. antitrust doctrine, market power alone is not sufficient to establish an antitrust violation. It must be shown that that power is abused. You’d be hard-pressed to find cardholders who think they’ve been abused by Mastercard or Visa.

Antitrust suits against America’s payment networks are nothing new. The first significant antitrust salvo, Nabanco’s suit against Visa, challenged credit-card interchange fees. In 1984, Judge Hoeveler held that the relevant market consisted of all retail-payment services including cash, checks, and travelers’ checks, ATM cards, check-guarantee cards, and private-label and general-purpose credit cards; that Visa did not have market power; that interchange was necessary; and that the pro-competitive benefit of interchange offset any noncompetitive effect.

Antitrust suits brought by the Department of Justice in 1998, and by merchants in 1996, were more successful and put Mastercard and Visa in enterprising trial lawyers’ crosshairs.

In 1998, the DoJ challenged Mastercard’s and Visa’s membership “duality,” that is, banks participating in the governance of both bankcard associations. The action also cited the networks’ bans on member banks participating in competitors American Express and Discover.

Judge Barbara Jones’s watershed 2001 decision narrowed the relevant antitrust market to branded general-purpose payment networks, and ruled Mastercard and Visa had market power. While Justice lost on duality, Jones ruled that Mastercard’s and Visa’s prohibitions on member banks participating in American Express and Discover were anti-competitive and violated the Sherman Antitrust Act.

Then, in 2003, the Visa Check/MasterMoney class-action antitrust case—also known as “the Walmart case,”— settled. Mastercard and Visa paid $1 billion and $2 billion, respectively, and agreed not to tie debit and credit card acceptance; to mark debit cards; and to reduce debit interchange by a third for five months.

That case put blood in the water for trial attorneys.